When you're picking out a DVR for your home, there's a pretty short list of candidates—TiVo has its new 6-tuner DVRs, or you can get something from your cable provider, or you can roll your own. But consumer-grade DVRs don't really scale all that well for media companies that need to record and process lots of TV. When you've got 30 or more channels that you need to be recording simultaneously, your cable company's DVR isn't really up to snuff anymore, and it's time to call in the big guns.

Houston-based SnapStream makes a line of DVRs that scale to truly silly sizes—its products are the monster trucks of the DVR world. If you watch TV at all, you've almost certainly already seen what SnapStream can do—popular shows like The Colbert Report, The Daily Show, The Soup, and tons of others are customers, using 30+ channel DVRs to record dozens and dozens of TV shows simultaneously in order to integrate clips from those recorded shows into their own.

But SnapStream's boxes do a lot more than simply record TV—they're actually a home theater PC geek's dream. Because Snapstream works so closely with media production companies, its DVRs sport functionality that no consumer set could possibly get away with having. For example, a SnapStream cluster is just as good at repackaging, transcoding, and distributing content for re-use as it is for recording it in the first place—functionality you won't find on a consumer-grade DVR. The system also gives users the most amazing TV guide access we've ever laid eyes on, wrapped in a simple and almost ludicrously fast GUI.

Ars recently spent some time at SnapStream's Houston-based office to learn more about what the company's products do and how they do it. What we found was actually pretty surprising: the privately held company only has about twenty employees, but its products are everywhere—not just in media, but in just about any industry that needs to record and catalog video, including local, state, and federal governments.

From HTPC app to enterprise hardware

SnapStream actually got its start as Beyond TV, an early HTPC application that let Windows users record cable TV to their hard drives. The application was not free, but it was a more cost-effective way for users to get TiVo-like functionality without having to actually pay for a TiVo or other full DVR.

By 2006, the proliferation of DVRs packaged with cable services began to significantly limit BeyondTV's mass-market appeal, since prospective customers could simply get a DVR bundled with their service rather than needing to build their own out of a spare PC. Looking for new opportunities, the BeyondTV folks began looking at companies using TVs and DVRs in a corporate environment, asking them what kind of a product they needed to make their businesses work.

"It really boiled down to just recording more things at a time than your typical DVR can do," explained Aaron Thompson, SnapStream's president. "Being able to record, say, all of the news channels was something companies were interested in... The Daily Show, Colbert Report, and so on all use it to record a bunch of stuff, find what they want to make fun of, and quickly get it into their editing bays to get it on air."

Prior to SnapStream, the big media companies were using isolated DVRs to record all the different television shows they needed to capture. "You look at these guys and you'd see two racks full of TiVos, and it's like 'okay, on this day, this show is on this TiVo, and on the next day the next day's show is on this other TiVo,' and it was a very manual and intensive process....being able to sit down at a single interface and find everything instantly was a big change for them."

SnapStream's approach was to consolidate and scale up. Rather than relying on racks of isolated DVRs, SnapStream's enterprise DVR clusters together multiple capture servers that all pool together their storage. The servers run Windows Server 2008R2 and the proprietary SnapStream application, and they each contain a stack of hard disk drives in a RAID 5 4+1 configuration. The SnapStream application uses Microsoft SQL Server for storing metadata, and recorded video files are stored on the NTFS-formatted file system as regular files. Larger customers can also use existing SAN or NAS systems as file stores—the SnapStream application is simply an application, relying on the operating system itself for file access, and so anything Windows can use as storage, SnapStream can use.

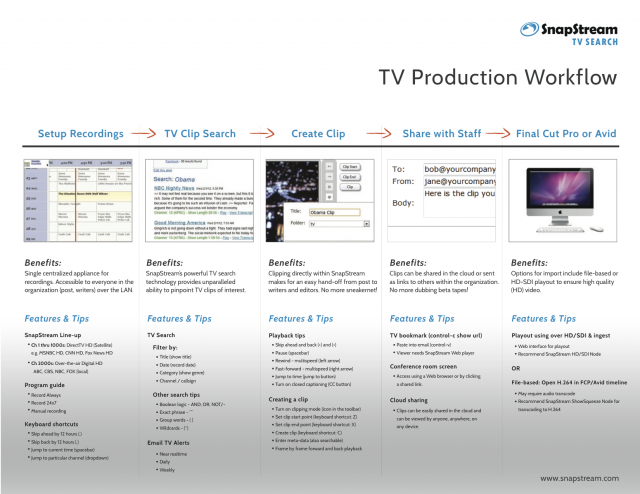

Video is typically ingested into the SnapStream DVRs directly from a cable feed at 480p, 720p, or 1080i through component inputs on heavy-duty QAM capture cards (typically costing up to $1500 each), thus bypassing the need for CableCard or any other type of integration with the cable infrastructure. However, this isn't always the case—many of SnapStream's media customers that share parent companies also share broadcast-resolution digital assets directly with each other over high-bandwidth private WAN links, skipping the cable network all together. The SnapStream DVRs can transcode and scale video from and to a variety of formats and resolutions and can even be used to output data over SDI, so that recorded clips can be seamlessly integrated into a TV show's production workflow.

The ability to record dozens of video streams isn't worth much without the ability to locate the things you're looking for among the pile of recorded shows, and SnapStream has an answer here, too: rather than rely on armies of interns to watch and catalog all the recorded TV, SnapStream peeks into the recorded shows' closed caption data and can search the entire recorded library for video based on keywords in the closed captions.

Caption search

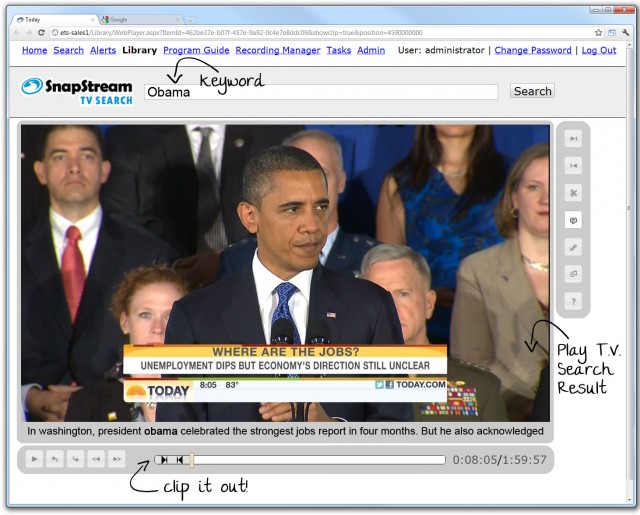

Seeing this in action was quite cool. To provide a quick demonstration, the SnapStream guys logged into one of their lab DVR clusters via its Web interface, then performed a search for "Obama." The search interface and results are formatted similarly to Google search results, with a quick textual blurb and a link. In this case, because the lab cluster had several days' worth of recorded TV from a number of local TV stations, we got quite a few hits on "Obama" as a search term. Clicking on any of the links took us directly to the TV program that contained the term, with the playhead ready to go right at the point in the program where the word was mentioned. The closed captions themselves were displayed to the right of the video.

At this point, SnapStream's functionality really began to diverge from a consumer DVR. While I was watching, SnapStream Director of Engineering Jason Baumeister quickly positioned a set of brackets around a 15-second portion of the show and clicked a "Share" Button; he typed in my Ars Technica e-mail address, and within a few seconds my phone buzzed. In my inbox I had a link pointing back at SnapStream's servers that I could tap and, over my phone's 3G connection, watch a properly transcoded version of the clip Baumeister had just selected for me.

The clip itself is treated as a separate object on the SnapStream DVR cluster, too; Baumeister and Thompson described how many of the media customers make extensive use of clipping in the run-up to production on their own TV shows. Folks involved with planning the evening run of The Soup, for example, can sit in a conference room with their laptops or tablets and quickly make and discuss clippings from the day's recorded reality TV shows, collaboratively dicing out the juiciest (soupiest?) bits of reality TV and assembling a rough playlist very quickly by searching for keywords, creating clips, and sharing them with each other.

Closed caption search aside, the system also features far and away the slickest TV guide grid I've ever had the pleasure of witnessing. SnapStream systems pull programming guide data from Tribune Media Services, just like most other programming guides do, but the way it displays the data is utterly utilitarian and supremely functional: within the SnapStream Web interface, the programming guide is a very simple AJAX-driven draggable grid. The grid actually reuses technology from a previous SnapStream project called Couchville, which SnapStream discontinued in 2007. It looks and acts just like a regular DVR or Web programming guide, showing channels along one axis and times along another, but it can be dragged with the mouse and programs in the grid can be clicked to record, or clicked to play if they're already recorded. It's instantly responsive. No fluff, no cruft, no graphics—just a beautifully functional program guide. As with so many things about the system, it's a feature that consumer DVRs and HTPCs desperately need and almost certainly will never get.

The reason for this and for the other features' absence on the consumer side is easy to articulate: at its core, the goals of the SnapStream system are at odds with the things that cable providers want DVRs to be able to do. "A lot of what our solution does is what they don't want you to do—I want to record this at one central place and view it at thousands of different locations, or take a portion of it and e-mail it out. That's exactly what the limitations [on consumer DVRs] are there to prevent," said Thompson.

SnapStream, though, operates sort of on the other side of the curtain. The customers who are in the position to perform grand feats of copyright infringement are actually the exact same customers who would be filing the copyright infringement lawsuits. As long as the open recording and sharing of full broadcast-resolution TV stays in the realm of the media production companies making the TV in the first place, no one gets upset. And SnapStream let me know that they currently have no private individuals as customers—no crazy billionaires with SnapStream systems in their crazy billionaire mansions, so the systems all remain in the hands of ostensibly responsible, non-infringing entities.

reader comments

61