Hamid Djadda is leaning out over the handrail on the stepped concrete grandstands of what was once one of the most famous raceways in Germany.

Opened in 1921, it was a marvel of the burgeoning automotive age: two long straights, capped by a hairpin turn and a wide arc just before the finish line. On race days, up to 4,000 people watched daring racing car drivers pilot the latest advancements in auto engineering, breaking land speed records – or crashing to their deaths trying.

After nearly a century hosting sporting events including motorcycle races and Formula One, the Automobil-Verkehrs und Übungsstraße (Automobile Traffic and Practice Road, or Avus) held its last race in 1998, and the concrete grandstands were left to slowly disintegrate.

But 20 years later, the cars still zoom by: the racetrack is now part of the 115 autobahn in west Berlin, and for passing motorists the grandstands are a roadside head-turning oddity, fenced off, crumbling and covered in graffiti.

“It’s a unique building worldwide,” Djadda says over the roaring traffic, “because you’re so close. Look!” He jabs his arm at a huge truck passing in the near lane. It’s almost near enough to touch. “You cannot just tear it down.”

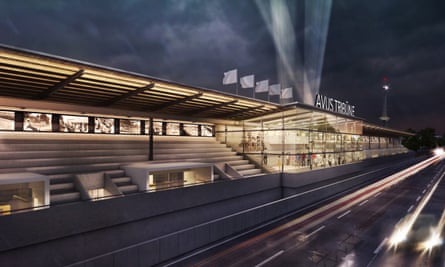

Nearly three years ago, Djadda bought this roadside anomaly – which is now a listed historical building – and with Hamburg architect Christoph Janiesch has devised an ambitious plan to revive the grandstands. Djadda wants to turn the decrepit hall and announcer’s box into a glass-walled event venue and bar overlooking the autobahn. Offices are to be built into the voids beneath, lit by a dozen skylights in the stands. These will double as large vitrines lining the structure’s 240-metre length, and will display vintage automobiles where the crowds once sat, like a high-speed drive-by museum of the history of the car.

The finished building will be a motoring spectacle, but the construction of the project itself will be a lesson in ingenuity. Work began earlier this year with the removal of the rotting wooden roof, which Djadda plans to replace in the spring. Due to the grandstands’ proximity to traffic, construction is only allowed during certain short windows and completion is targeted for the racetrack’s centenary in 2021.

Christoph Rauhut, director of the Berlin state conservation authority, welcomes the project. “These are difficult buildings to protect,” he says. “What is planned is not so much a massive intervention but really a rediscovery of the original quality of the building.”

“It has a high symbolic value,” agrees Richard Vahrenkamp, a logistics expert who has written extensively about German transportation.

Although Vahrenkamp is hopeful Djadda’s project will preserve this piece of autobahn history, he remains sceptical about the business model: “There’s so much traffic, it’s not really a nice place for events.”

Plenty of people expressed doubts during the two years it took to secure building permits, says Djadda. “People warned me, of course. And some said ‘you’re completely crazy’. I’m not the typical real estate developer.”

Born in Iran and raised in Hamburg, Djadda ran a crystal glass business in Thailand for two decades before returning to Germany, where he is involved in businesses ranging from marzipan confections to tin signs. Although he describes the grandstands’ purchase price as “not so much”, Djadda expects the renovation to cost between €5m and €7m (£4.5m-£6.3m).

He says the passing traffic is precisely the site’s appeal: the grandstands naturally draw a lot of attention: “I see this much more as a marketing place. Don’t forget, there are 93,000 cars every day driving by.”

Conceived in 1913, the Avus was a privately funded effort to support the German automobile industry. Progress stalled by the first world war, but building resumed in 1919 and the first race was held in September 1921. On days without races, it was used as a toll road: wealthy Berliners paid 10 Marks for a quick route to their lakeside homes along what is considered to be Europe’s first controlled-access motorway.

Vahrenkamp says the road was also used as a testing ground for new materials such as macadam, asphalt and concrete. After the Nazis came to power in 1933, lessons learned on the Avus guided the development of the national freeway network. “It was the example for autobahn planning and design,” Vahrenkamp says. Later integrated into the autobahn system, the Avus went on to host both races and regular vehicle traffic through the 1990s.

The racetrack’s observation tower is now a truckstop restaurant.

“For some people it is an important, historic place,” says employee Manuela Mattner as she points out black-and-white racing photos plastered on the tabletops. “It’s the first thing you see when you drive into Berlin.”

Djadda is betting on the value of that unique location.

“Right now, due to the regulations, I cannot put any advertisements here,” he says. “It would distract from the driving. But once you have autonomous cars, then I can put anything I want. Then it’s a huge value. In that world, I would use it for advertisement.”

Whether that world materialises any time soon is an open question, but Djadda is confident the project will succeed: “This will be even more monumental, I think, once we have only self-driving cars.”

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to join the discussion, and explore our archive here